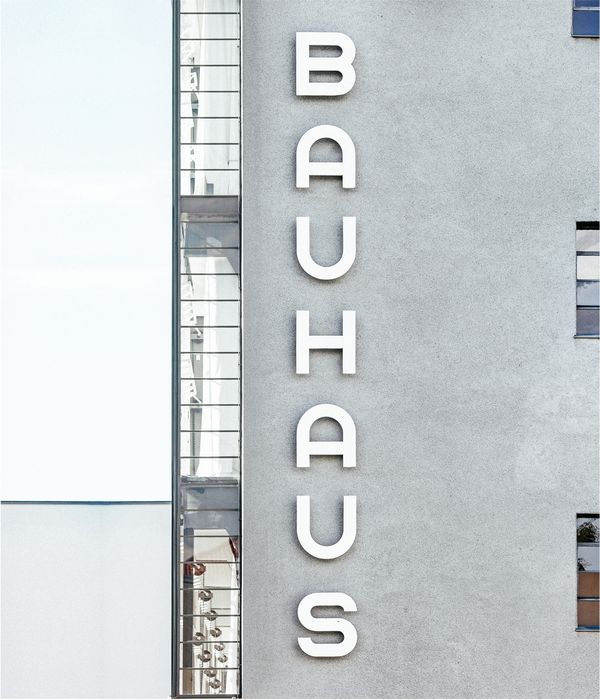

Modern Movement

Best known for its clean-cut design and geometric formations, the Bauhaus embraced fine art alongside advancing commerce in the early 20th century.

Words Imogen Smith

Photography Ross Sokolovski and DLewis

A creative visionary who couldn’t draw, Walter Gropius could be considered a juxtaposition. And yet he was the founder of Bauhaus, considered one of the most impactful artistic movements of the 20th century. Anni Albers, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Marcel Breur were all artists who emerged and thrived in this movement, a movement which fostered a relationship between art, society and technology.

Initially trained under the architect Peter Behrens, Gropius was also introduced to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who later became the third and final director of the Bauhaus school and who’s ‘less is more’ ethos defined architecture for the modern era.

Literally translated, Bauhaus is a combination of two German words: bau (building) and haus (house). The name suggests the idea of a collective working under one roof to build a new society; a remedy to ease post-war anxieties and the soulless rigidity of modern manufacturing.

As a student of the Bauhaus, the emphasis on learning was through intuition and experimentation. Both traits were adopted by a young Anni Albers, who enrolled at the school in 1922 during its most impoverished years. With limited choices for further study, Anni began working in the weaving workshop, under the guidance of Martin Brandenburg, and later, Paul Klee, who taught at the school for almost the entirety of the 1930s alongside his Russian friend, the notable artist Wassily Kandinsky, both of whom were pivotal to the school’s teaching of abstract design and colour theory.

Helped by their instruction, Anni quickly embraced the technical and aesthetic challenges of weaving and pushed the boundaries of the craft through experimentation and modern design. Characterised by their geometric shapes and use of vivid colours, Anni’s works may look familiarly uniform on the surface but look more profoundly at the closely-woven threads of each wall hanging, rug or print and we can understand how radical her creations were at the time and remain to be today.

Image: Ross Sokolovski/Unsplash

Anni’s work not only prompted new technological advances in the weaving workshop at the Bauhaus, she also paved the way for a ‘cultural reassessment of fabrics as an art form’ and her influence is still felt among fashion designers such as Paul Smith and Roksanda Ilinčić. The two celebrated fashion designers profess to use her methods as a reference for their own collections. ‘I’m most inspired by Anni’s very experimental and pioneering approach to using unexpected materials and fibres’, said Smith, who created a Scottish cashmere jumper, scarf and blanket inspired by one of Anni’s graphic and untitled wall-hangings from 1925, in celebration of the artist’s 2018 retrospective at the Tate Modern in London.

Image: Dlewis33/iStock

Reuniting fine art with functional manufacturing, it was this belief which underpinned the Bauhaus’ most visionary and impactful works, including the painting Red Balloon by Paul Klee, depicting a whimsical, geometric composition: Marcel Breuer’s Club Chair (Model B3) designed as a modernist take on a classic upholstered chair from the 19th century, and Marianne Brand’s Model No. MT 49 teapot.

In appreciating these creations both collectively and individually, we can understand how influential the Bauhaus movement was at the time and still is today, even 100 years after the school’s founding. It continues to inform different design disciplines and traces of the Bauhaus effect can still be seen everywhere from Tel Aviv – which counts over 4,000 Bauhaus-style buildings in its stark-white skyline – to Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House in Chicago.

There have been many monumental and significant artistic movements which have trickled into various fractions of creativity, but Bauhaus is specifically unique. It led to the rethinking of the fine arts as visual arts and reconceptualised the concept of ‘art’, likening it to science.

He may not have been able to draw but Bahaus founder, Walter Gropius, clearly knew how to make a mark within modern art and modern thought.